Move over Morlocks, humans are headed to your neighborhood

Twenty feet under Delancey Street in Manhattan is a trolley terminal that hasn’t been used in 65 years—a ghostly space of cobblestones, abandoned tracks and columns supporting vaulted ceilings. An ideal place for the city to store, say, old filing cabinets. Yet when the architect James Ramsey saw it, he imagined a park with paths, benches and trees. A park that could be used in any weather, because it gets no rain. That it also gets no sunlight is a handicap, but not one he couldn’t overcome.

If the 20th century belonged to the skyscraper, argues Daniel Barasch, who is working with Ramsey to build New York’s—and possibly the world’s—first underground park, then the frontier of architecture in the 21st is in the basement.

There are advantages to underground construction, not all of them obvious, says Eduardo de Mulder, a Dutch geologist. Although excavation is expensive and technically challenging in places like the Netherlands with a high water table, underground space is cheaper to maintain—there are no windows to wash, no roof or facade exposed to weather. The energy cost of lighting is more than offset by savings on heating and cooling in the relatively constant below-ground temperature. Cities with harsh winters or blazing summers have been at the forefront of the building-down trend. Underground real estate in crowded Shanghai and Beijing, expanding at around 10 percent a year since the turn of the century, is projected to reach 34 square miles in the capital by 2020. Helsinki’s master plan calls for significantly expanding its tunnels and more than 400 underground facilities, which includes a seawater-cooled data center.

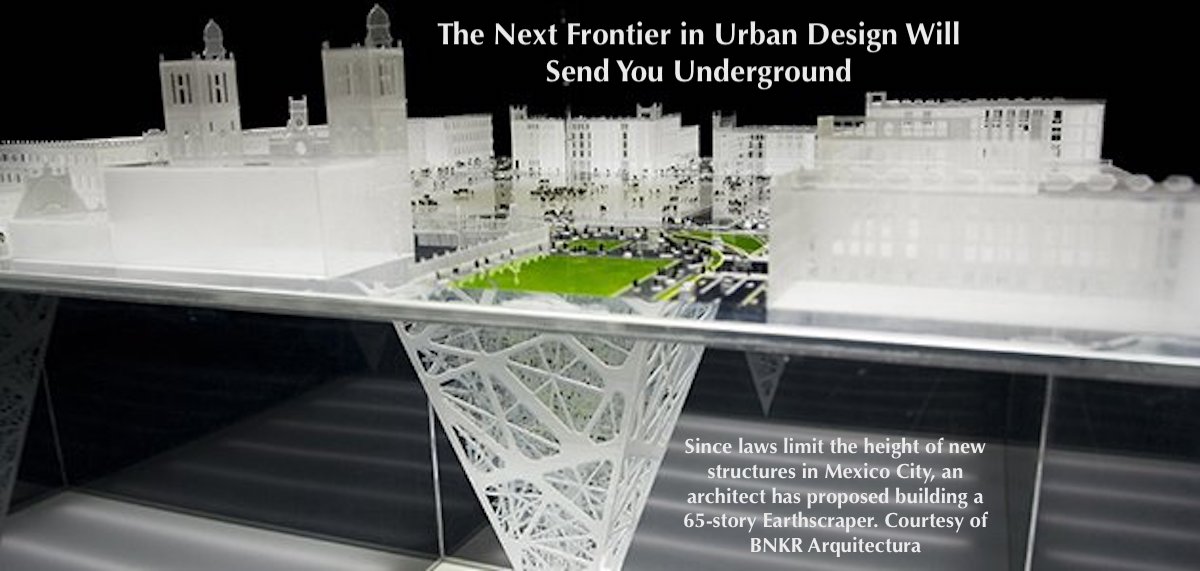

Of course, you give something up to relocate underground, namely, windows. Even de Mulder thinks below-ground living (as distinct from working and shopping) has a large obstacle to overcome in human psychology. Mexico City architect Esteban Suarez’s proposed Earthscraper, an inverted pyramid designed to go 65 stories straight down, with a central shaft for daylight and air, remains unbuilt. But is the idea of underground living really so unheard of? Early human beings lived in caves, and in Turkey, the ancient Derinkuyu Underground City could have sheltered as many as 20,000 people on at least eight levels extending more than 275 feet below ground. The complex included rooms for habitation, workshops, food storage, even livestock pens; stone slabs sealing off corridors and stairs suggest that it was meant for refuge from invaders.

To bring sunlight to the cobblestones beneath Delancey Street, Ramsey has invented what he calls “remote skylights.” Pole-mounted receptors above the street, linked by fiber-optic cables to panels in the ceiling of the space below, illuminate space with genuine photons from the sun itself (rather than the simulacrum of daylight from light bulbs). He and Barasch call their proposal the Lowline, capitalizing on the success of the High Line, a West Side park that took over an unused rail trestle. With a small staff working out of Ramsey’s architecture office, they have begun building political support and raising the $60 million they estimate it will cost. “This will be a beautiful, sanitary, well-lit, vibrant space,” says Barasch. “It just happens to be below ground.”